Archive for February 2014

Don’t Worry, Be Quiet

Paul Kagame is the sixth President of Rwanda, having taken office in 2000. He appears to be rather firmly rooted in place.

Asked last year if he would step down when his term ends in 2017, he said, “Don’t worry about that.” Pressed to explain, he said simply, “No. It is a broad answer to say you don’t need to worry about anything.”

— “America’s 25 Most Awkward Allies”, Politico Magazine, http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2014/02/americas-most-awkward-allies-103889.html

We can all learn a thing or two from a man like that.

And, by the way, we apparently need a refresher on the difference between a friend and an ally.

Smoke Detectors Made Difficult

When the smoke detector battery starts to fail, the smoke detector starts beeping very loudly. This can interfere with your ability to sleep. The manufacturer intended that.

Evidently, the previous owners of the house confronted this issue. They weren’t always good at getting the smoke detector down in such a way as to be able to get it back up as designed. No worries: Glue it back up. By the time the battery wears down again, we will have sold the house and it will be the new owners’ problem how to get in there and change the battery.

I know that they encountered the issue before. The house has about ten smoke detectors. I found one upstairs that was badly taped to the mounting fixture.

The purpose of this post is to express my gratitude for their forethought.

.. Use Words When Necessary

When I write, I want to verify the quotes and references I use. Even when material is common knowledge, that does not establish that the common knowledge is factually correct. Thus, I began to research this quote which is attributed to St. Francis of Assisi:

Preach the Gospel at all times. Use words when necessary.

So did St. Francis ever really say that?

There does not appear to be direct evidence that he said those exact words:

This is a great quote, very Franciscan in its spirit, but not literally from St. Francis. The thought is his; this catchy phrasing is not in his writings or in the earliest biographies about him.

— “Great Saying But Tough to Trace”, St. Anthony Messenger, http://www.americancatholic.org/messenger/oct2001/Wiseman.asp

St. Francis founded the Franciscan order. In Chapter XVII of his Rule of 1221, he did write, “Let all the brothers, however, preach by their deeds.”

This emphasis on exemplification has got up the noses of several commentators:

It is a quote that has often rankled me because it seems to create a useless dichotomy between speech and action.

— Glenn T. Stanton, “FactChecker: Misquoting Francis of Assisi”, The Gospel Coalition, http://thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/tgc/2012/07/11/factchecker-misquoting-francis-of-assisi/

This author is neither in the world nor of it if he has never experienced a dichotomy between speech and action in everyday life.

Much of the rhetorical power of the quotation comes from the assumption that Francis not only said it but lived it.

The problem is that he did not say it. Nor did he live it. And those two contra-facts tell us something about the spirit of our age.

— Mark Galli, Speak the Gospel“, Christianity Today, http://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2009/mayweb-only/120-42.0.html

Actually, the correctness of the quotation would not be impaired by the speaker having at times failed to live up to it. Humans, being imperfect, do that.

If we are to make disciples of all nations, we must use words. Preaching necessitates the use of language.

— Ed Stetzer, “Preach the Gospel, and Since It’s Necessary, Use Words”, Christianity Today, http://www.christianitytoday.com/edstetzer/2012/june/preach-gospel-and-since-its-necessary-use-words.html

The preaching is rather empty without credibility conferred by actions.

Judging by the way these and other authors have reacted — abreacted, really — I must conclude that this quote has struck a nerve. If St. Francis did not really say the quotation attributed to him, he should have.

Persecution, Hard Work and the One Percent

In late January, the venture capitalist Tom Perkins wrote a brief letter to the Wall Street Journal where he drew a comparison between the attitudes toward Jews in 1930s Germany and attitudes toward high-income people in America today:

Writing from the epicenter of progressive thought, San Francisco, I would call attention to the parallels of fascist Nazi Germany to its war on its “one percent,” namely its Jews, to the progressive war on the American one percent, namely the “rich.”

— Letter to the Wall Street Journal, 24 Jan 2014, http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304549504579316913982034286

Perkins was widely criticized for this comparison, and subsequently apologized for the specific analogy, saying:

Kristallnacht should never have been used. The Holocaust is incomparable.

— Tom Perkins, quoted in “VC Perkins: Ignore Protesters Against Silicon Valley’s Rich”, The Wall Street Journal, http://blogs.wsj.com/digits/2014/02/14/vc-perkins-ignore-protesters-against-silicon-valleys-rich/

Chicago businessman and investor Sam Zell pitched in this month, saying:

The 1 percent work harder, the 1 percent are much bigger factors in all forms of our society.

— Sam Zell, quoted in “Sam Zell: ‘The 1 percent work harder'”, The Chicago Tribune, http://www.chicagotribune.com/business/breaking/chi-sam-zell-1-percent-20140206,0,2270803.story

Working Hard as Justification

J. T. O’Donnell recently raised an interesting challenge to claims of working hard:

Aren’t we all guilty at times of thinking we work harder than others? And, doesn’t that make us prone to thinking we deserve more than others too?

See the problem this creates?

I think it’s very similar to a marriage. When both spouses think they are contributing more than the other, they often end up divorced.

— J. T. O’Donnell, “Do You Work Hard?…Really?…I Don’t Think So.”, http://www.linkedin.com/today/post/article/20140130151835-7668018-do-you-work-hard-really-i-don-t-think-so?trk=mp-reader-card

She has a point: how do you substantiate claims of who works harder? More importantly, what claim does it give you if it’s true?

I don’t think it’s fair to say that Sam Zell works harder than people I know. I do think it is accurate to say that what Sam Zell works hard at is more remunerative than the activities at which people I know work hard.

This whole argument about working hard is an unfortunate distraction. You can find a thousand people who are willing to work hard, provided there is no risk, before you find one person who is willing to take risks. Under a properly working capitalist system, the person who takes the risks will have greater returns than the people who work hard but do not take risks. The person who takes risks is the bottleneck resource. Without her, nobody makes progress.

Neither is job stress a justification. There is stress that pays $20 an hour, and stress that pays $500,000 a year. Choose your stress. Where I used to live, my polling place was a vocational school, where there was a sign that said:

If you have a job with no aggravation, you don’t have a job.

Risk-taking, Hard Work and Persecution

Perkins’ argument is more interesting, particularly in the light of European history. Yes, there is no current comparison between the current political context and the Nazi persecution of Jews after Hitler came to power in 1933. However, Hitler did not force his racial program on a hostile polity. There was more than enough of an anti-Semitic tradition extant in Germany to build upon.

Economic Roots of European Anti-Semitism

Jews had been marginalized in Europe legally, socially and economically going back to the Middle Ages. Often they were forced to find ways to make a living that the Christian population was not interested in pursuing, and they became good at these. Many kingdoms prohibited Jews from owning land, and guilds frequently closed their doors to Jews. Thus, Jews were often relegated to trading, which had lower status than farmers or artisans.

The Third Lateran Council (1179) declared anyone lending money for interest anathema; this position was restated by several subsequent popes. There was no reason to make a business of lending money without any return, and this put a brake on capital formation. Since money-lending was proscribed to European Christians, the field was left open to Jews. Somebody had to do the lending or the economic development of the West would not have occurred. The same governments that upheld the papal injunctions against money-lending had no qualms regarding living beyond their means and borrowing the difference.

Historical persecution of Jews also led them to value learning. While wealth could be confiscated by the local lord or prince, no one could take away your learning.

Thus, Jews were left very well positioned to succeed in an economy where capital was the bottleneck resource, ability to manage economic risk was a key success factor and learning was a greater asset than physical strength or personal bravery. Their successes and the means by which they attained them were often resented by their gentile neighbors.

The farmers and artisans of medieval Germany begat the farmers and craftsmen of industrial Germany. These people had a tradition of hard work, and built a reputation for industriousness throughout Europe. European kings, such as those of Poland and Hungary, settled outpost towns with Germans.

Is there any wilderness on earth which Germans could not turn into a land of plenty? Not for nothing did Russians say in the old days that “a German is like a willow tree — stick it in anywhere and it will take.”

— Alexander Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago Volume 3, p. 400.

However, economic advances arising from commercial and industrial development increasingly exposed the Germans to situations where Jews, who did not typically perform physical labor to the extent that the gentile Germans did, used their learning and understanding of risk to pass the Germans by economically. The Germans deeply resented this (as did other European gentiles). Instead of seeing the situation in terms of the Jews taking advantage of their abilities and new economic opportunities, the Germans viewed the situation as the Jews taking advantage of the Germans.

While Jews in Germany were more integrated into society than were Jews in Poland or Russia, one should not construe that German non-Jews fully accepted them. Far from it. Jews were often subject to social disparagement, ostracism and ridicule. The program of the Pan-German League for war aims in 1914 did not see the Jews as equal Germans who would share in the spoils of victory, but as a separate tribe that could be resettled in some out-of-the-way marginal lands nobody really wanted [Woodruff D. Smith, The Ideological Origins of Nazi Imperialism, pp. 176-8].

Of approximately 555,000 self-identified Jews living under the Kaiser in 1914, about 100,000 served in defense of the Reich and 12,000 laid down their lives [http://www.germanjewishsoldiers.com/epilogue.php]. However, this did not necessarily influence the opinions of Germans. Regiments were drawn geographically, and a soldier from rural Pomerania or Bavaria could easily serve the full four years without being mixed with Jewish soldiers from Hamburg or Berlin. Non-Jewish Germans often did not necessarily give German soldiers of Jewish faith credit for their participation, preferring to remember the trader or banker who profited during the war. A record of honorable service in the Kaiser’s army would offer no protection from the Nazis.

Economic Forces after 1918

After 1918, Central Europe was filled with defeated nations who were suffering profound economic contraction and emergent nations whose prospects were little better. The reduced economic prospects heightened competition, and social and philosophical forces caused people to gather together along “ethnic” lines, ignoring whatever integration of Jews and non-Jews had already occurred. The economic situation, in short, got nasty as people found themselves competing to divide a smaller pie.

This condition was not limited to Germany, and exhibited some curious effects. In Hungary, for example, there was the curious phenomenon of educated people making the running in anti-Semitic agitation:

When a university graduate went to a business to look for a job, he usually found that if there were openings, he was either not trained for them or not willing to accept them for fear of a loss of prestige. … When such positions were unavailable, the frustrated applicant was likely to blame his unemployment on the discriminatory attitude of a Jewish owner.

A similar scenario obtained in the case of the civil service. … Hungarian university graduates often submitted applications only to find the ranks of officialdom so hopelessly overinflated as to permit no increase, and found it convenient to blame their failure on those Jews (relatively few in number) who had gotten there first. The frustrated Hungarian aspirants, who would rather live in Budapest on handouts from friends and relatives than take a job in the provinces or learn a practical, perhaps even a manual, profession, formed the core of right-wing anti-Semitic thinking. It is a tragic irony that the educated sector of the population was most inclined to find emotional hatred the best substitute for logic and reason.

— E. Garrison Walters, The Other Europe: Eastern Europe to 1945, p. 216.

In Germany, the racial overtones of competition were already well established by 1920. The destruction of savings and pensions in the inflation of 1923 was followed by the progressive proletarianization of craftsmen and shopkeepers through the twenties.

The Jews became the embodiment, on a scale unprecedented in history, of every ill besetting state and society in the final stage of the Weimar Republic. … Yet the main charge against the Jews was that they dominated such spheres as banking, business, real estate, brokerage, money-lending and cattle-trading.

— Richard Grunberger, The 12-Year Reich: A Social History of Nazi Germany 1933-1945, p. 15.

The Grounds for Comparison

The Kristallnacht pogrom of November 1938 signaled a turning point. Prior to this, although the legal oppression of the Jews was continually ratcheted up, the regime maintained a weakly plausible deniability regarding brutality and murder. The pogrom marked the point where what had been a cold war against the Jews turned organized, methodical and violent. It was no longer possible to pretend that those taking the lead in such attacks were hotheads who were exceeding their orders.

There is no stretch of the imagination by which the current situation in America can legitimately be compared to Kristallnacht. Even the name of the latter is itself a relatively sanitized euphemism for the reality on the street. Much more than glass was broken that night: at least 91 Jews died as an immediate result of the violence, with about 30,000 being interned in concentration camps.

Direct comparisons between our intellectual climate and that of Germany in 1938 are not supportable, but what about the Germany of 1928? Here there is evidence upon which to build an argument supporting comparisons. The government was not in the racial hatred business, but there were an abundance of very loud people with influence and access, calling for the people to take retribution on a subset of their number for imagined wrongs and a large segment of the polity predisposed to respond favorably to this message.

It is true that politics were much more violent in Germany, with all parties having to maintain paramilitary organizations to prevent intimidation of their own supporters while attempting to incite fear among their opponents. We do not have a similar situation here at this time. However, this is not a necessary precondition for the identification and prosecution of campaigns against supposed enemies of the people.

The economic stereotyping of Jews as parasites blended with wounded national pride, the Volksgemeinschaft ideal, romanticism of an idealized rural and pre-industrial past and a search for scapegoats into a particularly noxious cocktail. The message that “you have been betrayed, victimized by others” fell on fertile ground after the unrewarded sacrifices of the Great War and the ruinous economic dislocations of 1923 and 1931. People living in Germany at that time at least did not have the well-documented historical example of what a modern, cultured, industrial nation is capable of becoming. We don’t have that excuse.

Often the Jews who were rounded up between 1935 and 1942 would be made to perform physical labor, as degrading as could be found, as part of their punishment for being Jews. The locals who were organizing this would say something like, “Now you Jews are doing an honest day’s work.” Nor was this atavistic attitude limited to racial targets.

Obligatory training camps for entrants into the learned professions were instituted, with a similar end in view. Press photographs of junior barristers scrubbing the floor on such a course at one of these camps and captioned ‘Labour is an indispensable method of education’ carried the implication that, however well-tutored, these Herren Referendare were not acquainted with work as the man-in-the-street was and were now being forcibly familiarized with it for their own good.

— Grunberger, p. 47.

Sweat Equity

Which brings us back to the original topic: the belief that only those who perform hard labor are deserving of the fruits of production. This is the root of economic errors such as the labor theory of value.

Large numbers of people in urbanized, modern economies must be familiar with basic principles and proof against being manipulated by unscrupulous demagogues who play on envy, ignorance and irrationality. If these people are allowed to succeed in setting up their game of Let’s You and Him Fight, all of us will lose not only our standards of living but our liberty.

Three Theories of Trade

Why do people engage in trade? What do they gain from trading? There are three basic theories about the nature of trade. The choice among these is tied to the believer’s ethical stance and worldview. The belief chosen says more about the believer than it does about the subject matter.

Strictly speaking, trade is the exchange of goods or services for other goods or services. A person who accepts money only does so with the expectation of being able to exchange the money for goods or services (wealth) at some future time.

For purposes of discussion, however, consider bilateral agreements concerning the purchase of goods or services for money, in order to keep the discussion simple. Money flows one way, and goods or services the other. More complex transactions, having more forms of consideration moving between more sets of hands, do not alter the basic fundamentals, and only obscure the main points.

Implicit Coercion

One theory of trade insists that the stronger party takes advantage of the weaker party through implicit coercion. An example of this line of thinking: the employer has a stronger position than the employee, who “needs” a job in order to put food on the table, and can therefore dictate terms to the employee.

This position does not stand up to analysis. The worker is seeking a job, but is not compelled to accept this job. The word need is used with a double meaning here, which is why I have put it in quotes. It is an amphiboly: a semantic ambiguity. In order to get on in the world, one chooses to trade services for money, but it is still a choice. Furthermore, there is no compulsion to take any one specific opportunity.

One should remember that the larger a market that a worker has for his services, the more choices he has and the stronger his bargaining position will be with any one potential employer. A worker who has limited skills has fewer potential buyers of her services. A worker who has a high cost structure, with large fixed payments for home and auto loans, may be able to get a number of jobs that will not allow him to keep his head above water financially. However, none of these factors constitute implicit coercion. The alternatives, including relocation and bankruptcy, may not be attractive, but they are there nonetheless.

People — particularly people who operate from positions of powerlessness — often use language of compulsion where it is not warranted. He must stay at his job, she has to host Thanksgiving dinner, they had no choice but to rent that apartment. However, there are always choices, although they may be categorically unacceptable to the decision-maker.

Unfortunately, it is a bootless effort to attempt to reason with people who are invested in victim thinking. To challenge their thinking on this is often to challenge their whole justification for living as they have done. They won’t hear it, and they will be impervious to attempts to convince them that they are not being coerced.

Zero-Sum Net Effect

Another theory of trade assumes that, since the participants are exchanging value for value, there is no net effect on either participant. Both came out with the same utility which which they went into the exchange. However, this begs a simple question: why bother to trade at all? Trade requires effort. The participants have to gather information, enter the market, locate one another and arrive at a mutually acceptable agreement. If this provided no improvement to either party over the initial condition, there would be no reason to engage in trading.

Positive-Sum Net Effect

The fact that both participants opt to do the deal indicates that each believes that s/he will be better off trading than not trading. This is the only alternative that explains why trade occurs.

A Practical Example

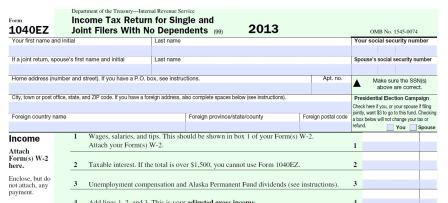

The IRS received almost 143 million individual tax filings for 2010. In an effort to make this burden more manageable for both itself and the taxpaying public, the IRS introduced the Form 1040A in 1980 and the Form 1040-EZ in 1982. These forms are simplified and have restricted applicability. For example, in 2013 the taxpayer could not have dependents or taxable income over $100,000, among other restrictions, in order to use the Form 1040-EZ.

The form is only 12 lines long. It is deliberately designed to be simple: E-Z, like its name. Yet it is a substantial part of the business of paid tax preparation chains to help people fill these out.

Are the tax prep chains ripping off poor people? Are the taxpayers stupid? Neither conclusion is supported here.

Value

What value are the firms providing to these consumers?

- Specialization: The tax preparer completes these forms many times in a single year, while the individual does so once. The preparer can become more familiar with the requirements of the form.

- Service: The preparer relieves the taxpayer of a chore that the latter would rather not perform.

- Confidence: The taxpayer is confronted with an obligation that has emotional baggage. What if I don’t do it right? The preparer relieves the taxpayer of this emotional burden. Many of the larger firms advertise, as a selling point, that they will send representatives with you to the IRS if you are audited (Would the IRS audit a taxpayer who made $30,000 and had no deductions and no capital gains? Who knows for sure?).

Is this value proposition worth what the firms charge to prepare a 1040-EZ? Evidently to some people, not to others. Nobody makes taxpayers use a paid preparer in any form. I have seen people standing by the roadside dressed as the Statue of Liberty, trying to entice customers into the tax preparer’s office, but I have never seen people with nets who forcibly capture customers and carry them into the tax preparer’s office.

Is there implicit coercion? The government has withheld your tax money. Even if you, at the end of the year, do not owe any taxes at all, you have to file to get the withheld money back. Nevertheless, you could make the economic decision that the hassle of filing is not worth the value of the refund. Furthermore, you don’t have to use a preparer. The IRS has gone the extra mile to make it easy on people who are in simple filing situations to file their taxes. The taxpayer has to take responsibility for the choice.

Is it a zero-sum transaction? No, the taxpayer obtains more utility from the value provided by the preparer, including intangibles mentioned above, than he gives up in money. Otherwise, he wouldn’t take the trouble of going to the preparer.

Ralph Kiner

Ralph Kiner, who I grew up listening to, died yesterday at age 91.

My favorite Ralph Kiner story was his negotiation with Branch Rickey for a raise after the 1952 season. Kiner recounted his achievements: his home run title, his having driven in over 100 RBIs.

Rickey, who was notoriously tight with money, replied, “Son, we finished in last place with you, and we can finish in last place without you.”