Archive for May 2013

Liberal Capitalist Democracy

When words have no defined meanings, it is hard to hold an intelligent conversation. It should really be no surprise that our national conversation is so shrill and so inconclusive, when we can’t even agree on what the words mean.

Liberal

The words liberal and liberty have a common root, the Latin liber, meaning free. In late medieval England, a liberty was a piece of land in possession of a lord or abbot, into which royal officials such as sheriffs may not enter without permission of the possessor [Roberts and Roberts, A History of England, vol. 1, p. 339]. By 1630, the meaning of the word liberty had been broadened to mean freedom for anyone from domination by the king and court. A person who supported the rights of persons against the divine right of the monarch became a liberal.

The word was also used by opponents to include persons who did whatever they wanted without moral restraint, seeking to imply that those who would defy the will of the king today would act without any limits tomorrow. However, by 1700 there was general understanding that such a person was not a liberal, but a libertine.

In nineteenth century terms, the opposite of a liberal was a reactionary, someone who reacted to threats to established order and privilege. Liberals sought freedom of speech, assembly and worship, and to end slavery and involuntary servitude. Liberals wanted all people (well, initially all men, but the program did broaden to include women over time) to have the freedom to choose their residence, occupation and avocations.

In the United States in the 1930s, political activists who were not at all liberal adopted the term for themselves in order to give themselves the appearance of continuity with existing political traditions. They sought to paint themselves as the heirs of liberalism and their opponents as the party of reaction. The success model for this was Lenin: in 1903, after a split within the Russian Communist Party, he and his followers began calling themselves bolshevik (majority) and their opponents menshevik (minority), even though it was quite the other way around. Lenin and his followers had lost the vote, were marginalized within the party and ultimately sought exile abroad. However, through endless repetition, they have succeeded in being known to history as Bolsheviks.

Irving Babbitt had seen this coming: in his 1924 book Democracy and Leadership, he devoted an entire chapter to “True and False Liberals.”

It is a matter of no small importance in any case to be defective in one’s definition of liberty; for any defect here will be reflected in one’s definition of peace and justice; and the outlook for a society which has defective notions of peace and justice cannot be regarded as very promising. [p. 262]

The history of the twentieth century has demonstrated the wisdom of this observation.

Most people who we identify as liberals are not really liberals at all. They are prepared to sacrifice liberal goals such as individual self-determination and rule of law to ends that they consider to be higher priorities. This in itself does not invalidate their programs, but we should not mistake them for liberals. It confuses everyone’s thinking.

Capitalist

Capitalism was named by Marx and primarily defined by its detractors. It seems that those who understand capitalism go out and make money, while those who do not write content complaining how unfair the system is.

Partly as a result of the ideological conflicts during the Cold War, capitalism has typically been identified with private property, but not all economic systems featuring private ownership of property are inevitably capitalist. Manorialism, which was the economy of feudalism, included private property but also enforced servitude and restricted economic growth. Fascist states have typically allowed private ownership of property, but restricted how the individual could make use of it. You can have all the headaches of owning and caring for property; we’ll just tell you what you can and cannot do with it.

Capitalism could not take root until ordered conditions such as rule of law and enforcement of agreements over time — contracts — had been firmly established. Even today, in countries where one cannot count on enforcement of a contract, economic development is next to impossible.

The deployment of capital necessitates risk. Lenders have relatively low risk; they are senior to investors in their legal rights to recover their money. Investors have greater risk than lenders, and expect greater rewards when successful.

Owners have the greatest risk of all. Being an owner just means that you get paid after everyone else is paid, if there is anything left to pay you with. If not, you get the losses.

A person who can form capital and manage risks in its use can obtain rewards far greater than a hard-working person who takes no risks. This is the part that Marx, who was wedded to the labor theory of value, did not comprehend. Marx, along with many others, could not understand why a hard-working laborer should be rewarded less than a man who sent his money out to work for him. The answer is that you can find a thousand persons who are willing to work hard for every one person who is willing to take risks. However, without the person who is willing to take risks, you don’t get the benefit of capital. At best, you have people piling their surplus up and storing it under the mattress. At worst, you have a peasant society, where people eat their surplus when times are good and starve en masse when times are bad.

It is human nature to try to fob the risk off to someone else but keep the reward. However, this breaks capitalism. An economy that allows this is not capitalist, but something rather different. Theodore Lowi noticed this decades ago:

Privileges in the form of money or license or underwriting are granted to established interests, largely in order to keep them established, and largely done in the name of maintaining public order and avoiding disequilibrium. The state grows, but the opportunities for sponsorship and privilege grow proportionately. Power goes up, but in the form of personal plunder rather than public choice. It would not be accurate to evaluate this model as “socialism for the rich and capitalism for the poor,” because many thousands of low-income persons and groups have profited within the system. The more accurate characterization might be “socialism for the organized, capitalism for the unorganized.”

— Lowi, The End of Liberalism, 2nd ed. (1979), pp. 278-279.

Lowi developed his characterization of the new political economy this way:

Permanent receivership would simply involve public or joint public-private maintenance of the assets in their prebankrupt form and never disposing of them at all, regardless of inequities, inefficiencies, or costs of maintenance.

— Lowi, p. 279.

The enterprise in question need not be on the verge of bankruptcy or a candidate for liquidation. It could simply be large enough to represent a risk of dislocation to the economy if it were to collapse: too big to fail.

This could be called anticipatory receivership suggesting that the policy measures appropriate for the concept give the government a very special capacity to plan. Permanent receivership can be extended outward to include organizations that are not businesses. If there are public policies which are inspired by or can be understood in terms of this expanded definition, then we have all the elements of a state of permanent receivership.

— Lowi, pp. 279-280.

This is not capitalism at all. There is no creative destruction; it is a goal of policy to avoid destruction in any form. There is no risk, provided you are included in an approved group. There is no profit-and-loss discipline. And all organization, including but not limited to business enterprises, become “public-private partnerships” directed to obtain public policy goals. Properly understood, this is a species of corporatism:

A U.S.-style corporate state has arrived unsung, unheralded and almost never mentioned. The emergence of corporatism has to do with the parallel emergence of Big Labor, Big Agriculture, Big Business, Big Universities, Big Defense, Big Welfare and Big Government, all operating in a symbiotic relationship. It also has to do with the growth of modern social policy, with the government assuming a great role in the management of the economy, with the greater emphasis on group rights and group entitlements over individual rights, and with the growth of a large administrative-state regulatory apparatus.

— Howard J. Wiarda, Corporatism and Comparative Politics, p. 147.

Main Street may be mostly capitalist, but Wall Street and K Street are solidly corporatist.

Democracy

There is a material difference between a democracy and a republic. Although many people use the terms interchangeably, they are not in fact synonymous.

In The Federalist #10, James Madison makes clear that a republic can offer safeguards against mob rule that a democracy cannot.

A republic, by which I mean a government in which the scheme of representation takes place, opens a different prospect, and promises the cure for which we are seeking. Let us examine the points in which it varies from pure democracy, and we shall comprehend both the nature of the cure and the efficacy which it must derive from the Union.

The two great points of difference between a democracy and a republic are: first, the delegation of the government, in the latter, to a small number of citizens elected by the rest; secondly, the greater number of citizens, and greater sphere of country, over which the latter may be extended.

Neither Madison nor most of his contemporaries — possibly excepting Jefferson — saw direct democracy as a desirable outcome. This viewpoint was not limited to southern planters:

It is a besetting vice of democracies to substitute publick opinion for law. This is the usual form in which masses of men exhibit their tyranny. When the majority of the entire community commits this fault it is a sore grievance, but when local bodies, influenced by local interests, pretend to style themselves the publick, they are assuming powers that belong to the whole body of the people, and to them only under constitutional limitations. No tyranny of one, nor any tyranny of the few, is worse than this. All attempts in the publick, therefore, to do that which the publick has no right to do, should be frowned upon as the precise form in which tyranny is the most apt to be displayed in a democracy.

— James Fenimore Cooper, The American Democrat (1838), p. 71.

The framers of the Constitution sought safeguards to prevent the tyranny of the mob. They divided the government into distinct branches that could block the initiatives of the others. They also set specific limits on what each branch could do.

The framers also divided power between the federal government and the governments of the sovereign states. An unfortunate casualty of the civil war was this balance. The Secession Crisis discredited the concept of states’ rights, and there was a subsequent erosion of state power. In 1913, the 17th Amendment was ratified; this replaced the election of senators by state legislators with election by the citizens of the states directly. This, together with the increasing cost of running a statewide election campaign, has turned the Senate from the legislative body representing the states and a counterweight to the House of Representatives into an American House of Lords. The attempt by Caroline Kennedy to obtain the seat from New York being vacated by Hillary Clinton in 2008 was symptomatic of this state of affairs.

Even Irving Babbitt must be questioned; after all, he titled his book Democracy and Leadership, not Republicanism and Leadership. What did he really want? He clearly did not support egalitarian democracy:

If we go back, indeed, to the beginnings of our institutions, we find that America stood from the start for two different views of government that have their origin in different views of liberty and ultimately of human nature. The view that is set forth in the Declaration of Independence assumes that man has certain abstract rights; it has therefore important points of contact with the French revolutionary “idealism.” The view that inspired our Constitution, on the other hand, has much in common with Burke. If the first of these political philosophies is properly associated with Jefferson, the second has its most distinguished representative in Washington. The Jeffersonian liberal has faith in the goodness of the natural man, and so tends to overlook the need of a veto power either in the individual or in the state. The liberals of whom I have taken Washington to be the type are less expansive in their attitude toward the natural man. Just as man has a higher self that acts restrictively on his ordinary self, so, they hold, the state should have a higher or permanent self, embodied in institutions, that should set bounds to its ordinary self as expressed by the popular will at any moment. The contrast that I am establishing is, of course, that between a constitutional and a direct democracy.

— Babbitt, pp. 272-3.

More properly, it is the contrast between a republic and a democracy.

A direct democracy is, in fact, a sentimentalist fantasy. Each citizen must allocate her time among the demands of citizenship and other interests and occupations she may have. Some citizens will make the economic decision to relinquish participation in governance, delegating their voice to others and accepting the results. There can never be an effective direct democracy, because even if everyone can participate, not everyone will. This is not alleviated by technology; it is a natural consequence of the different priorities and time allocation decisions of the citizens. As Madison believed, a republic in which citizens were represented by those who had chosen to commit their time to the responsibility is the only practical approach to self-government.

The sentimentalist also ignores the possibility that some citizens may not view political responsibility as a good at all. Anyone who is out in the world paying attention knows some persons who would rather relinquish power to others than have to take responsibility for their own decisions. Such persons are easily led, and their scope for malignant effects on the body politic are much greater in a democracy than a republic.

Before calling for reforms to increase democracy, we must review whether democracy is something we really want. Our predecessors who founded this country did not, and there is no evidence that they were wrong.

No, It Hasn’t Peaked Quite Yet

Jon Lovett was a speechwriter for President Obama for three years. He left Washington to write for the unsuccessful TV series “1600 Penn.” Last week, he delivered the Commencement Address at Pitzer College in Claremont, CA. An excerpt from that speech was published in The Atlantic: http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2013/05/life-lessons-in-fighting-the-culture-of-bullshit/276030/

I believe we may have reached “peak bullshit.” And that increasingly, those who push back against the noise and nonsense; those who refuse to accept the untruths of politics and commerce and entertainment and government will be rewarded. That we are at the beginning of something important.

I, however, think Churchill is more apropos:

Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.

We have not hit the peak yet. We are not yet at the beginning of something important, but we are reaching the end of something very trivial, very fake, very self-referential.

The business of bullshit, like that of illegal drugs, is demand-driven: as long as there is demand, someone will supply it, because, for some people, supplying bullshit beats working. Thus, in order to estimate when we are over the peak, we have to watch for signs of a fall-off in demand. People have to stop participating in the transaction, rewarding others for bullshitting them.

In any prosperous society, people prefer to avoid accountability and whisper sweet nothings in their own ears. They prefer the view in the mirror to the view out the window until the latter is too menacing to be ignored. Therefore, the prosperity has to go away to the point that people start paying attention to what is outside the window again. Conditions have to get sufficiently scary and compelling. How far a society has to fall depends on the society. Some never get their faces out of the mirror until they hit the pavement and go splat.

I would like to think we can clue in before we fall that far. What would be some signs that we had crossed over the peak and are on the downslope?

One indication would be the existence of fewer speechwriters. One questions whether the politicians really believe half of what is written for them.

Time Allocation

A necessary precondition is for ordinary people to be paying attention. Both the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street are early, faltering, blind beginnings. We need more people paying attention, allocating their time to being subjects rather than objects in their economic and political lives.

Where would the time come from to allocate to this? It would have to come from leisure, because there is no where else to obtain it. Therefore, one set of indicators would be consequences of people allocating their time away from leisure. This would manifest itself as dislocations in the entertainment business, as there would be a sudden glut of entertainment relative to demand. Positive signs in this area would be:

- Contraction in major sports, such as the National Football League (In the National Hockey League, there is already one franchise known to be on life support).

- A periodical such as People or Us ceasing publications.

I don’t have anything against entertainment. I watch pro sports myself. However, if people allocate their time away from leisure and toward investing in themselves and their communities, there just isn’t going to be enough leisure to go around and support all the entertainment channels that currently exist.

Controls

A common cause of being lied to is failure, as a process owner, to establish adequate controls. Whether you are a parent, a manager or a citizen, how do you know what is being done when your back is turned? You create controls to allow you to know, and to allow the people subject to the controls to know that you know.

Locks keep honest people honest.

— Computer security proverb

A good leading indicator would be the sight of parents establishing and enforcing adequate controls for their kids.

It would also help if more people took a greater interest in what their elected officials are doing. Transparency doesn’t help if no one is looking. It would be great to hear that the server at http://thomas.loc.gov/home/thomas.php was overwhelmed by demand of voters to find out what their elected officials were creating and what their voting records were.

Overcoming Sentimentality

“It is work,” as Buddha says, and not love, as the Western sentimentalist would have it, “that makes the world go round.”

— Irving Babbitt, Democracy and Leadership, p. 247.

If we are to get control over the conning and lying, we must stop setting ourselves up to be conned and lied to. The sentimentalist, being naturally expansive, wants to open all doors and hope for the best. He thrills to words and phrases that sound pleasing, without thinking through what they really mean. Then, when the nasty surprise comes at the end, he is blindsided. How could anyone have known?

Avoiding the outcome we are experiencing requires a lot of work. It requires thinking through the consequences fearlessly, peering down the road before turning down it. It requires taking responsibility for more of our own lives. It requires cleaning up our little corners of the world ourselves, so the great campaigns and crusades are unnecessary.

A population that was less sentimental would not necessarily be hard, cold or merciless. It need not result in uncharitable behavior. But the charity would be deliberately granted or withheld.

More to the point, as a less sentimental people, we would be more demanding on ourselves. We would set more limits and exercise more restraint. We would do the work to understand the consequences of what we were doing before we did it. Behaviors that exemplify these qualities would be powerful indicators that we, as a people, were ready to be done with the lies and the cons.

Lovett praises the earnestness and authenticity of the graduates. Earnestness and authenticity are not enough. Any medieval mob that roved the land, pillaging towns and killing people, was earnest and authentic. So were the followers of Soviet Communism in the 1920s and 1930s, until they were in their turn liquidated by Stalin, often with the assistance of other earnest and authentic followers.

We need more than this. We need skepticism without cynicism, although what we have is quite the other way around. We need to be equipped and ready to do the inner work to make ourselves proof against the untruths. We need the intellect to know what to do and the will to do it.

Fiat Money

Here is a simple but effective presentation on fiat money:

http://www.marketplace.org/topics/business/whiteboard/fiat-money-it-has-nothing-do-car

The problem with a gold standard is that the monetary base, which is the amount of money in circulation, can’t expand to keep up with the economy. Then there is too little money chasing the available wealth, which depresses the economy.

The problem with fiat money is that the monetary base can be expanded by the government to be anything. It need have no relation to the actual economy. Then there is too much money chasing the available wealth, which inflates the economy.

It’s a Favor Doing Business With You

I encountered two incidents and a video this week. Even though the incidents are isolated, they illustrate a pattern that I am observing. The video nicely reinforces it.

No Job-hoppers

I attended a meeting where the speaker was a professional recruiter, commonly known as a headhunter. He recounted an experience where the client, who was seeking a person to fill a position, was very explicit about their desire to not bring in a person who had a record of switching from job to job. They wanted someone who had at least five years with the same employer.

Here’s the catch: the client was seeking to fill a four-month contract engagement. One-sided much?

So if you’re the person who has five years with the same employer, why would you leave to take a four-month contract? Given that you have wanted to stick around one company for five years, why would you be attracted to such a short-term opportunity? And, having taken the contract and completed it, would you not have ruined your record, so that the same company would not consider you for a further position because you no longer meet the qualifications?

Guess the Number I’m Thinking Of

I heard about this through a real estate agent who was representing the buyer. The agent had put an offer in on a house on the buyers’ behalf. The sellers’ agent says that the sellers do want to sell their house. However, the sellers’ agent indicated the offer was not acceptable, but in no specific aspect. The buyers made a full price offer, so we can eliminate the “insulting offer price” excuse. The seller’s agent refused to clarify what would make the offer acceptable, and unequivocally stated that the sellers would not respond with a counteroffer, because “they are not putting their signatures on an offer.”

How does a real estate transaction come to completion under these conditions? For a seller who is reputedly motivated, this sure doesn’t look like the behavior of someone who wants to go to contract. Do the sellers and their agent expect the buyers to throw contracts at them until they happen to get it right? What buyers would be stupid enough to engage in this? Maybe the buyers’ agent should deliver the offer with a fruit basket and implore the sellers to find the offer worthy of consideration, like an ambassador to a Renaissance prince. Be careful not to turn your back to the sellers as you bow and scrape your way out the door.

The Pattern

The pattern that I am seeing is one of people doing business in an increasingly one-sided manner, with no thought for how their conduct comes across to the other party.

A young child has an ideothetic view of the world; he sees himself as the only subject. He is the center of his universe. Only he has needs, wants and plans. Everyone else exists only to fit into these needs, wants and plans. When they fail to do so, they are defective, useless jerks.

By the time the child becomes an adolescent, his worldview should have become allothetic. He should be capable of seeing other people as players with their own goals and desires that they wish to fulfill. He should know that, in order to realize his plans in cooperation with others, he must account for their plans and offer the others a chance to realize them.

Which brings us to the video:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xmpYnxlEh0c

It is an excerpt from a speech David Foster Wallace gave to the graduating class of Kenyon College in 2005. Without using the ten-dollar words, he calls for an allothetic worldview:

The point is that petty, frustrating crap like this is exactly where the work of

choosing is gonna come in. Because the traffic jams and crowded aisles and long checkout lines give me time to think, and if I don’t make a conscious decision about how to think and what to pay attention to, I’m gonna be pissed and miserable every time I have to shop. Because my natural default setting is the certainty that situations like this are really all about me. About MY hungriness and MY fatigue and MY desire to just get home, and it’s going to seem for all the world like everybody else is just in my way. And who are all these people in my way? And look at how repulsive most of them are, and how stupid and cow-like and dead-eyed and nonhuman they seem in the checkout line, or at how annoying and rude it is that people are talking loudly on cell phones in the middle of the line. And look at how deeply and personally unfair this is.If I choose to think this way in a store and on the freeway, fine. Lots of us do. Except thinking this way tends to be so easy and automatic that it doesn’t have to be a choice. It is my natural default setting. It’s the automatic way that I experience the boring, frustrating, crowded parts of adult life when I’m operating on the automatic, unconscious belief that I am the center of the world, and that my immediate needs and feelings are what should determine the world’s priorities.

Becoming an adult only requires time; all you have to do is stand there and get old. Growing up is a choice, and requires hard work. Not everyone wants to do it.

If I choose to think this way in a store and on the freeway, the problem is I am also building thinking habits. Before long, I am also thinking this way when selling a house or when hiring.

I’m not saying that you have to give away the store to the person you’re doing business with. I’m saying that you should think about why the person in front of you should want to talk to you, to work for you, to do business with you.

I have known salespeople who had signs on their walls that said, “I can get what I want by helping other people get what they want.”

The Oversight

This poem was originally printed in the Akron Times, and reprinted in the Journal of Electrical Workers and Operators, January 1922, published by the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. Irving Babbitt reprinted the last stanza in the note on p. 222 of Democracy and Leadership.

The Oversight

There are many scores of schemers,

Poets, orators and dreamers

Who are working for the bright millennium;

But in spite of all their hoping,

Mankind still is blindly groping

And the Golden Era somehow fails to come.

If some special dispensation

Could bring wholesale reformation,

Revolutionize us mortals over night,

Why, the well-known species human —

Male and female, man and woman —

Soon would make this earth a planet of delight.

But, although we are improving,

We are sadly slow in moving

Toward the period of sinlessness and bliss,

And instead of lightly tripping

To the goal, our feet are slipping

And our program of redemption goes amiss.

So, I judge it is not treason

To advance a simple reason

For the sorry lack of progress we decry.

It is this: Instead of working

On himself, each one is shirking

And trying to reform the other guy.

Three Forces that Will Shape American Life

There are three forces that will determine our future. They are essential to our lives, and they are often misunderstood or underappreciated. They are ownership, accountability and risk.

Ownership

The term knowledge worker is generally credited to Peter Drucker, who had been writing about it back in 1959. There were knowledge workers before this: a military officer is a commander, but has also been a knowledge worker since at least Napoleonic times. Lawyers have always been knowledge workers. However, it was in the mid-twentieth century that knowledge work began to proliferate.

If you want to make your commanding officer look like an absolute fool, do exactly what he tells you to.

— Military precept

In order for a person to be effective in knowledge work, the person must be engaged. A person waiting to be told what to do will be a failure as a knowledge worker. For the person to be engaged, the person must feel that her contribution is wanted. You can’t have it both ways: you can’t have an engaged worker hanging on your every command. Without ownership of the task, engagement falls away.

Why is it that I always get the whole person when what I really want is a pair of hands?

— Attributed to Henry Ford

There has long been a tension in organizations over knowledge work. By its very definition, it does not admit detailed supervision. If the manager has to review every decision of the worker, then two are doing the job of one. The manager who attempts this will have a very small span of control. However, there is a conflict with the centripetal forces of the organization: status, privilege and the need for control.

The tension between ownership and control has never been fully resolved. Some management teams achieve a modus vivendi that allows their enterprise to succeed for a while, but ultimately the balance cannot be maintained. The organization either hardens into a controlling environment, or the lack of control causes it to burst at the seams.

That’s just how it always went with one of these new Silicon Valley hardware companies: once it showed promise, it ditched its visionary founder, who everyone deep down thought was a psycho anyway, and became a sane, ordinary place.

— Michael Lewis, The New New Thing, p. 47.

And sane, ordinary places get same, predictable results. Disengaged people hang around sane, ordinary places; engaged people leave at the first opportunity.

The problem also exists in the public space. The orthodoxy we learned in seventh grade civics says that power derives from the consent of the governed. Passive consent or active consent? It’s a harder question than it looks. From the evidence of recent experience, you can fool many more of the people much more of the time than we are comfortable with. But, having fooled them, you can’t credibly turn around and ask them to take responsibility for the results.

Accountability

You can find material praising accountability, but it is really more selective than commonly understood. Second-person accountability — accountability for you — is always a Good Thing. First-person accountability — accountability for me — is a trickier subject.

Clearly, when the outcome is positive, the person responsible is in favor of accountability. However, when the outcome is unfavorable, it becomes an orphan. There are always extenuating circumstances why I shouldn’t be held accountable for the bad outcome.

The American education establishment has shown thought leadership here, promoting the idea that only they can evaluate their own results. Only the professionals are equipped to hold themselves accountable. From this you make a living?

The problem with inadequate accountability is that no learning takes place. If no one is accountable, everyone does the same things they always did and hopes for a different outcome. “The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over, hoping for a different result.”

Risk

The story of the society over the past hundred years is the story of the attempt to remove risk from everyday life. It has not worked, and resulted in epic boredom. It has also caused people to no longer understand risk and how to manage the tradeoffs. The country has become risk-averse in to a level that cannot be sustained, that cannot allow it to function. We have also fixated on spectacular hazards with remote probabilities while being blind to less consequential hazards with higher probabilities.

Our modern middle class is the descendant of an older gentry composed of independent farmers, small businessmen, self-employed lawyers, doctors and ministers.

— Barbara Ehrenreich, Fear of Falling, pp. 78-79.

As Ehrenreich notes, independent farmers, small businessmen and self-employed lawyers faced business risk. The new middle class that arose since mid-century largely consisted of a credentialed salariat. This cohort is highly risk-averse but often does not recognize the risk it actually incurs. When I hear someone talking about buying stock in his own employer at market price, I know I am in the presence of someone who does not naturally think about risk.

Some nations have sought planning capacity by socializing production — one or more basic industries. Some may try planning by the socialization of natural resources, while others may socialize the delivery of central services. Some may socialize banks while others seek to socialize the distribution of goods. The United States has so far skirted all these alternatives in favor of socialization of its most valuable resource: risk.

— Theodore J. Lowi, The End of Liberalism (2nd ed.), p. 289.

At a macro level, the elimination of risk had produced, by 1960, a producer-centric economy with only the fiction of profit-and-loss discipline at the large corporate level. This ultimately resulted in bailouts for corporations such as Lockheed (1971) and Chrysler (1980). If the corporations were allowed to go under, where would all the workers go?

The economy can still be characterized as “socialism for the organized, capitalism for the unorganized,” as Lowi did in 1979. Patches of capitalism are observable in technology, where business mutates too fast for public policy and administration to keep up. The core of the economy, however, is managed with the goal of socializing risk. That is great for people who fail, but not so great for people who have to subsidize supporting those who fail.

Reducing risk through public policy, by regulation and underwriting, protects the underperforming and incompetent. It rewards them for holding the economy hostage. This approach suffers the same deficiencies as avoidance of accountability: what incentive does anyone have to learn, to do better next time?

These three basic forces — ownership, accountability and risk — are out in the wild having real, if unseen, effects on everyday life. Left improperly understood, the will upturn the carefully crafted society that has been built in partial ignorance of them.

Material Scarcity

Currently, there is an extensive debate going on both here and in Europe as to whether austerity or some form of pump-priming is called for to rectify the problems in the economy. Both sides have persuasive arguments, yet seem to be talking past one another. There seems to be a basic difference that is not being addressed. Without discussing it and resolving it, any agreement on conclusions is at best accidental and temporary.

Meanwhile, you can plug the term post-scarcity into the search engine of your choosing and find all kinds of material purporting to explain how we live in an age of abundance, and scarcity is a thing of the past. They people writing this content are often articulate and, one infers, intelligent. So why do they think this?

To answer these questions, we have to go back in history. We must return to the birth of macroeconomics and the creation of the world as we have come to know it.

Urbanization and the Great Depression

Prior to about 1850 here, or 1800 in England, the workings of the economy were very simple. Most people were engaged in the production of food. There were few factors of production available to produce anything other than food. Manufactured goods were relatively expensive compared to what they are today. The pre-industrial economy was basically a subsistence agricultural economy with relatively little surplus. Agricultural production was heavily dependent on labor, and that labor needed most of the product for its own maintenance. When conditions adversely affected food production, such as bad weather, famine ensued.

Through deliberate capital formation and risk management, the West crawled out of subsistence during the 1800s. As manufactured goods became cheaper, there was more scope to substitute capital for labor. The released labor moved to the cities and became available to produce more manufactured goods, and a virtuous cycle began. By 1920, there were more Americans living in towns and cities than on farms. This was not thought possible one hundred years earlier.

But around 1930, an inexplicable disaster arrived. Economic activity just stopped, and few people really understood why. Worse, it seemed that any rational action by any participant just made the situation worse. When people reacted to the uncertainty of future incomes by cutting spending, production or lending, these actions just accelerate the problem.

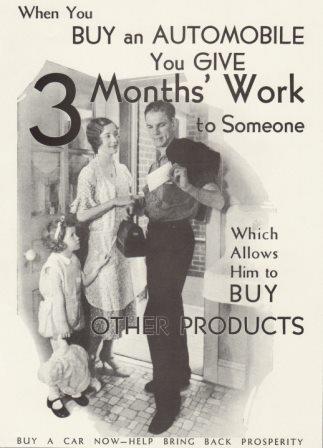

The government took to putting up posters such as the one above, exhorting people to buy consumer goods. But when their own incomes were uncertain, they didn’t dare make that kind of commitment. They pulled back, as did factory owners and lenders. In fact, the pro-cyclical policies of the Federal Reserve turned a bad business downturn into an epic depression.

At the height of the Depression, it seemed as if everything had come unglued. George Orwell captures the spirit and feeling in this often-quoted passage from The Road to Wigan Pier:

We walked up to the top of the slag-heap. The men were shovelling the dirt out of the trucks, while down below their wives and children were kneeling, swiftly scrabbling with their hands in the damp dirt and picking out lumps of coal the size of an egg or smaller. You would see a woman pounce on a tiny fragment of stuff, wipe it on her apron, scrutinize it to make sure it was coal, and pop it jealously into her sack. Of course, when you are boarding a truck you don’t know beforehand what is in it; it may be actual ‘dirt’ from the roads or it may merely be shale from the roofing. If it is a shale truck there will be no coal in it, but there occurs among the shale another inflammable rock called cannel, which looks very like ordinary shale but is slightly darker and is known by splitting in parallel lines, like slate. It makes tolerable fuel, not good enough to be commercially valuable, but good enough to be eagerly sought after by the unemployed. The miners on the shale trucks were picking out the cannel and splitting it up with their hammers. Down at the bottom of the ‘broo’ the people who had failed to get on to either train were gleaning the tiny chips of coal that came rolling down from above—fragments no bigger than a hazel-nut, these, but the people were glad enough to get them.

That scene stays in my mind as one of my pictures of Lancashire: the dumpy, shawled women, with their sacking aprons and their heavy black clogs, kneeling in the cindery mud and the bitter wind, searching eagerly for tiny chips of coal. They are glad enough to do it. In winter they are desperate for fuel; it is more important almost than food. Meanwhile all round, as far as the eye can see, are the slag-heaps and hoisting gear of collieries, and not one of those collieries can sell all the coal it is capable of producing.

The scene defied explanation. There was labor available to produce, but no labor was wanted. The means of production were there, but were laying unused and decaying. The raw materials were there, but there was no effort to extract them, for they could not be sold. What happened? More importantly, how could we make it stop, returning to the conditions of prosperity?

Demand Management

Intelligent, caring, earnest people looked at this situation and concluded that the basics of existence had changed: we were no longer constrained by the supply of wealth, but by the demand for it. They reasoned that, with the onset of urbanization and mechanization, we were now living in a time of material abundance, not scarcity.

This notion was not entirely new at the time. Catchings and Foster had done influential work in the 1920s developing the theory of underconsumption. Once the economy had reached a level where there was sufficient food, clothing and shelter for most people, would they become sated and just stop consuming? If they did, would the economy seize up? Could that be the underlying cause of the Depression?

Demand for wealth, not supply, was now seen as the bottleneck. As such, all the truisms of the past were inverted. The problem of economics would not be production, but distribution. Say’s Law had said that supply creates its own demand; in this new world, demand would create its own supply. Create the demand and the wealth to meet it would come from somewhere.

There was no effective competing theory available. Andrew Mellon’s liquidationism was manifestly unacceptable; these were real people — and real voters — living in Hoovervilles. The economic and political establishment was largely uninterested in the Austrian School.

While FDR never got the economy out of the hole until war production began in earnest in 1940, he was seen by the public to be Doing Something. Even though people who lived through it remembered that unemployment did not really return to normal until the war began, they still remembered FDR as the leader who saw us through the Depression. The grief captured on the newsreels when he died was genuine.

During the 40s and 50s, the new demand-based approach seemed to work. America outproduced its enemies in World War II. After the war, instead of a ruinous inflation and reversion to widespread unemployment that had been forecast, America experienced unprecedented prosperity.

As we entered the sixties, economic experts in government were confident that they could fine-tune the economy and smooth out the business cycle. Other thought leaders looked forward to a time when we would end poverty and include all Americans in prosperity.

So What Went Wrong?

There were several incorrect assumptions and faulty expectations baked into this cake; they shall be subjects of their own articles, as detailed treatment of them is outside the scope of this post. Among them:

- The fact that most of the developed world outside America had been reduced to pre-industrial conditions by the war was overlooked. Even Britain, who won the war, was impoverished by the necessity of beating plowshares into swords.

- The Johnson Administration tried to implement a guns-and-butter policy, launching the Great Society programs and conducting the Vietnam War.

- Political vote-buying accelerated, making ever-greater promises to larger numbers of people.

- There was a general hubris among the population, having overcome the Depression and won the War, leading to an exaggerated sense of what could be accomplished.

However, a fundamental problem that underpins many of the above is the fallacy of material abundance. Demand is not the bottleneck. No matter how affluent people become, their wants will still exceed the resources available to satisfy them.

The thinkers and would-be planners had thought that the masses would content themselves with having their basic material needs met, and demand would have to be stimulated. But that is not the way it played out:

They were heading out to the suburbs — the suburbs! — to places like Islip, Long Island and the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles — and buying houses with clapboard siding and pitched roofs and shingles and gaslight-style front-porch lamps and mailboxes set up on lengths of stiffened chain that seemed to defy gravity, and all sorts of other unbelievably cute or antiquey touches, and they loaded these homes with “drapes” such as baffled all description and wall-to-wall carpeting you could lose a shoe in, and they put barbecue pits and fish ponds with concrete cherubs urinating into them on the lawn out back, and they parked twenty-five-foot-long cars out front and Evinrude cruisers up on tow trailers in the carport just beyond the breezeway.

— Tom Wolfe, “The Me Decade and the Third Great Awakening”, Mauve Gloves & Madmen, Clutter & Vine (1976)

There was no underconsumption. There was no problem with demand. As long as the ability to pay, to provide value in exchange for value, was present, demand would take care of itself.

By the 1970s, we had the curious phenomenon of stagflation, a portmanteau of stagnation + inflation, which Keynesian orthodoxy preached was impossible. This was an early warning of troubles to come, and provoked some rethinking in economics. It barely rippled out to public policy.

In response to stagflation and the oil price shocks of the time, there was a brief notional flirtation with a return of focus to supply at that time, captured in the school commonly known as supply-side economics. However, this school had limited objectives, arguing for lower tax rates for the good of the collective — overall increase in growth and government receipts — rather than justifying these on an individualist basis. The mere recognition that supply had an active influence on the market was radical as it was. There was little rethinking of the macroeconomic focus on demand.

More recently, there was the downturn of 2001-2002, documented here: http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/watkins/rec2001.htm. At the time, it was recognized that consumers were carrying the economy. How were they doing it? They were dissaving. They were increasing their debt levels. They were withdrawing equity from their homes, through second mortgages, home equity lines of credit and cash-out refis. This had to end sometime, and ultimately it did.

The consumer couldn’t go the distance, but consumers don’t have a printing press. What about the government? The support of demand through government debt will ultimately fail as well. In FY 2012, Federal debt service was 5.5% of federal spending. Of the total of federal spending, only 81.8% was covered by revenue [based on data from http://www.usgovernmentspending.com]. Thus, revenue can’t keep up with spending and interest, the interest rolls into the balance due, and the interest compounds. Eventually, unless something gives, debt service will devour the federal budget.

The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest.

— attributed to Albert Einstein

Eating the Seed Corn

A fundamental but often-forgotten assumption behind macroeconomics is that the overriding majority of consumers are also the producers. They are producing the increased wealth, a share of which they take home as wages. These wages support the ability do satisfy the demand in the marketplace.

There will be a small minority of people who do not produce. Police are an example. Enforcing the law is very necessary, but it is not a wealth-creating activity. The economy has to create enough surplus wealth to pay for the enforcement of its laws and preservation of the security of its members.

An economy has to generate sufficient wealth to replace depreciated capital (such as equipment that wears out and has to be retired) and pay for governance and security functions (law enforcement, firemen, military) that do not create wealth. Any charitable transfers to people who cannot produce themselves must be subtracted here as well. If the wealth produced by the economy after these subtractions declining, the nation as a whole cannot maintain its standard of living. This is the current situation of the United States. We have been eating the seed corn for years.

Macroeconomics is in such theoretically bad shape that no one really knows how much wealth is out there or how much we produce. Few seem to care. Traditionally, we have backed into it with measures such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP). However, GDP should really be called Gross Domestic Expenditure. We count up how much we spent and assume that roughly that much wealth has been created. As the debt-financed economy of 2001-2007 demonstrated, it ain’t necessarily so.

The Material Qualifier

All the things of the physical world, including wealth, are subject to scarcity. These rules do not apply to things of the mental world, such as human energy, human attention, affection and ideas. The mental world is ruled by plenitude.

Consider human energy. Within limits, human energy becomes increasingly available as one expends more of it. This is witnessed by the saying, “If you want something done, give it to a busy person.” The more one does, the more one is capable of doing, until one reaches some boundary limit. This can be observed in everyday life.

Repent, the End Is Near

Common sense tells us that we cannot spend our way to prosperity, but macroeconomics was born in defiance of common sense.

If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.

— Herbert Stein (1916-1999)

The use of debt to prop demand up above the level of wealth creation that cannot support it cannot go on forever. It will stop, and it will stop in a very messy manner. Long-term decisions people have made, such as career investments, will be upturned. Plans that had seemed safe and prudent for decades will be suddenly exposed as reckless and foolhardy. There will be suffering, destroyed dreams, lost years.

The idea that we live in a time of material abundance is a delusion. It is a dangerous delusion, hazardous to anyone who imbibes it. No matter how much wealth exists in a community, people will always want more. They will not become sated on necessities; they will make luxuries into necessities. Except in times of extraordinary upheaval, such as an economic contraction, demand for wealth will always outrun supply.

An industrial economy is a very complex creature, a giant with feet of clay. It can survive some incredible stresses, but smaller forces acting “with the grain” can bring it down in a way that is very difficult to undo. This was the experience of the Depression.

Macroeconomics needs a comprehensive overhaul. There is currently no recognition of the foundation of prosperity in wealth creation. The study can be changed before its advice leads the economy to slam into a wall, or wait until after, when the evidence becomes too obvious for any but the truest of believers to ignore.

Mark Cuban on Higher Education

Mark Cuban, owner of Landmark Theaters, Magnolia Pictures and the NBA Dallas Mavericks, has written several articles on what he believes is a bubble in higher education:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/mark-cuban/will-your-college-go-out-_b_2558689.html

Cuban calls for a business focus on attending college:

The class of 2014 and beyond now has to prepare a college value plan. What classes are you going to take online that enables you to get the most credits for the least cost? What classes are you going to take at a local, low cost school so you can get additional credits at the lowest cost?

Then, with your freshman and sophmore classes out of the way, you can start to figure out which school you would like to transfer to, or two years from now, which online classes you can take that challenge you and prepare you for the areas you want to focus on. If you have the personal discipline you may be able to avoid ever having to step on a campus and graduating with a good degree and miracle of miracles, no debt.

That is a great idea, but I don’t know how many graduating seniors could actually execute it. There are some major risks that they would have to manage:

- Many students gear their performance up or down in response to their perception of the performance of students in their classes. Often there are people in local schools who are not really serious about their education. The student who wants to implement Cuban’s plan cannot be lulled to sleep in the low-cost school, or transfer to a more competitive four-year school will carry a nasty shock.

- This assumes that the student knows what course of study s/he intends to pursue at the outset and stays on that course. Many college freshmen do not know what they want to major in, or even what one does with the major once one graduates.

- The student must ensure that the credits taken before transferring will be honored by the school to which s/he intends to transfer.

The key caveat is provided by Cuban: “If you have the personal discipline, …” It can be done, but it requires a much greater degree of focus and self-motivation than many college-age students currently possess.

The one place where I really differ with Cuban is where he says:

College is where you find out about yourself. It’s where you learn how to learn.

There are more cost-effective ways to find out about yourself than attending college. And can we really afford to have 21- and 22-year olds who are still finding out about themselves? All your life you will be finding out about yourself; when is it time to join the grownup world and start producing?

As to learning how to learn, he is right that undergraduate college has been the place that people typically made the jump from being taught to learning how to learn, if they ever did. But it is an inefficient delivery system; look at how many people who attended college and are still waiting to be taught, rather than taking ownership of their learning. Moreover, we need that transition happening in high school. We need all citizens, whether or not they attend college, being able to take ownership of their learning.

Minimum Wage Laws: I Regret the Necessity

Earlier this year, when delivering the State of the Union address, President Obama called for an increase in the federal minimum wage from $7.25/hour to $9/hour. This provoked a fresh round of public debate on the minimum wage:

For purposes of this discussion, I am going to infer that the labor involved is unskilled, since skilled labor is sufficiently scarce to command a wage rate greater than minimum. I will equate unskilled with poor because the unskilled typically are the least wealthy of workers.

The classic economic argument against having a minimum wage is that it distorts the market and actually creates unemployment among unskilled people. Let’s examine.

The Economic Theory

Absent other constraints, the market sets wages by supply and demand. The theory says that the market allows participants to respond to conditions through the price mechanism. When prices of a good go up, more of that good is made available, but demand for it will fall off. When prices of a good go down, less of that good is made available, but demand for it will increase.

At some point the supply and demand curves. That is the equilibrium, the place where supply and demand are in balance. The amount of the good available at the price equals the amount of the good desired at the price.

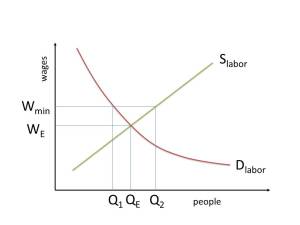

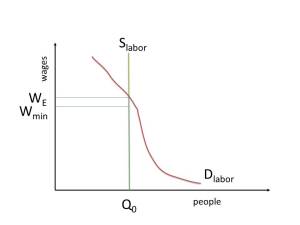

This is a picture of a market for unskilled labor. Unskilled labor is a good; there positive value in having an additional incremental unit of it. The horizontal axis represents a number of people, and the vertical axis represents a wage rate, which is a price for labor. I have drawn the traditional supply curve Slabor and demand curve Dlabor.

The market for unskilled labor is, in theory, just like the market for any other good. Left to its own, the market would sort itself out so that the equilibrium employment level QE and wage level WE would be reached.

Introducing a minimum wage distorts the market. The minimum wage must be above the equilibrium wage, or minimum wage laws would be irrelevant. Here, Wmin is the minimum wage. The minimum wage acts as a price floor, driving demand down and supply up an artificial amount. Demand for labor is reduced to Q1 at the minimum wage. Furthermore, price signals draw additional people into the market, so that the supply of labor is increased to Q2. Thus we have (Q2 — Q1) people who are involuntarily unemployed as a result of the minimum wage.

Follow all that? Excellent. Now let’s take it out in the real world and shoot it full of holes.

Price Signals?

The supply of unskilled labor consists of people who are unskilled. They don’t have a lot of alternatives to the unskilled labor market. Do they really get to respond to price signals?

The way I have drawn the previous diagram, as the wage rate goes down, some people who are unskilled withdraw from the market. Where would they go? How would they feed themselves? They typically do not have stored wealth to draw down while they are out of the market. Do they go on public assistance? That’s not OK; we want them working!

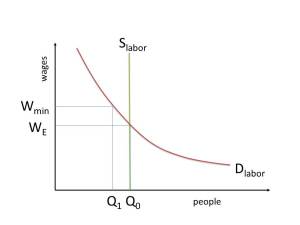

So the supply of unskilled labor cannot respond to price signals. There is only one allowable quantity of unskilled labor that can be available to the market: all of it. Thus the labor supply curve really looks like this:

Here, I have redrawn the supply curve so that all the unskilled labor, Q0, is available for work at any wage the market will allow. Where the supply meets the demand, there is still the equilibrium wage WE. At the minimum wage Wmin, demand for labor is reduced to Q1, just as before. Now the unemployment effect of the minimum wage is reduced to (Q0 — Q1).

Notice that the labor supply is not only forbidden to respond to price signals, but also to send them. If the sellers of labor are unsatisfied with the price, they are not allowed to communicate that by withdrawing supply. They have to take whatever the buyers of labor want to dish out to them.

I have called this a market, but it is not much of a market. There is no feedback loop between buyers and sellers. The buyers dictate what they are collectively willing to pay, and the sellers take it or leave it. Except it is not OK for the sellers to leave it, because they are not working. We would call them layabouts. We would challenge them for passing up the opportunity to earn anything. For the sellers, the terms are really take it or take it.

Here we have a group of people, the poor and unskilled, with a weak negotiating position. Most of them did not deliberately choose to be this way. Even those who made bad choices in the past may regret them now. We the People would be morally irresponsible to allow them to be trampled in the marketplace.

We are not done revising the model yet.

Buyer Behavior

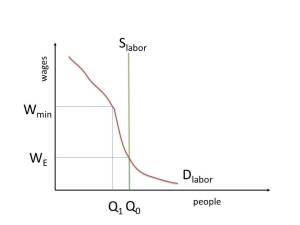

The demand curve doesn’t look quite right, either. The buyers of labor are typically small businesspersons and low-level managers in larger enterprises. They have their own notions of what they ought to be paying for unskilled labor: not very much. That gracefully sloping demand curve doesn’t really exist. Instead, the picture should look like this:

This is not the result of a deliberate conspiracy. Many of people buying unskilled labor just don’t think that unskilled labor deserves very much in the way of compensation. I know this because I have sat across from them at the lunch table and listened to them. They aren’t particularly mean-spirited; it’s just their worldview. They believe that unskilled people deserve about 35 cents an hour, a cup of coffee and a pat on the head. It is a consequence of outlook, similar to the New England mill owners of the mid-1800s who said it was immoral to pay high wages to workers because the workers would just dissipate the additional wages on booze.

The picture doesn’t change structurally from the previous picture. The big change is the outcomes. Without government intervention, the amount of labor employed would not be that much more, but the equilibrium wage WE is far below the minimum wage.

Never ask the accountants a question until you’ve told them what the answer should be.

— Business proverb

I know there are going to be readers who object to this because “the unskilled people don’t produce sufficient value to earn a higher wage.” I am not buying that argument. A compensation structure is a social system, an expression of whom we value and how much more or less than anyone else. In thirty years of working, including some time managing, I have not seen a scientific ability to relate how much someone is valued to how much value someone produces. I have not seen any significant ability to objectively measure how much value any employee produces for the firm. There is no more factual merit to this objection than there was to the assertion of the New England mill owners that laborers would drink any increment above subsistence wages. It is a rationalization for doing what people are already predisposed to do.

The Unnecessary Minimum Wage

It would be great if buyers of unskilled labor would leave something on the table, so that these workers would have more incentive to work. After all, these are poor people and they’re working. That’s what you want poor people to be doing, isn’t it?

I have not altered the supply or demand curves; I have just shifted demand such that buyers are prepared to pay more for unskilled labor. In this idealized alternative, the equilibrium wage WE is above the minimum wage and renders the latter irrelevant. All the available labor is absorbed by demand and there is no involuntary unemployment. All the unskilled labor that can work is making itself available for work and is working.

However, we are not there and have no prospect of getting there anytime soon. The labor supply has no ability to send price signals and influence buyer behavior to move the demand curve into this position. And I see no reasonable likelihood of buyers changing their behavior out of the goodness of their hearts. As such, it is unfortunately necessary to have a public policy so that we may protect the weak from being pushed to the wall.

The remedy for the evils of competition is found in the moderation and magnaminity of the strong and the successful, and not in any sickly sentimentalizing over the underdog. The mood of unrest and insurgency is so rife today as to suggest that our leaders, instead of thus controlling themselves, are guilty of an extreme psychic unrestraint.

— Irving Babbit, Democracy and Leadership (1924), p. 231.

Reality trumps theory. It is time for orthodox economics to recognize that the traditional analysis of minimum wage policy is wrong. It is based on assumptions that are inconsistent and beliefs that are not sustainable in the real world.

The Higher Education Bubble

You liked the dot-com bubble? You loved the housing bubble? Get ready for the higher education bubble.

Why Go to College?

Executives and representatives of colleges and universities write articles and give speeches in which they steadfastly maintain that they are not here to provide vocational training. OK, fine — but then, why would anyone with two neurons to rub together take out a loan to attend one?

I have known people who went to college to “broaden their intellectual horizons.” I have no problem with those who can afford the luxury of going to college for that reason taking advantage of the opportunity. But it was out of reach for me. I was there to enhance my ability to make a living, as are many of the other people who attend.

Some people go to get four more years before having to be responsible for themselves. In a 2005 article, the Wall Street Journal put the effective age of middle-class majority at 26 (http://online.wsj.com/article/SB110496649357818050.html). We can’t afford a society in which people are not expected to be grownups until 26. Not only will there be too few productive people carrying too many non-productive people, but a person who defers adult responsibility that long can easily defer it even longer.

Some people go to college to find themselves. There are more cost-effective ways to do this. Get out and work, and find yourself in the black rather than in the red. By now, even taking the grand tour of Europe is a cheaper way to find yourself than college.

Some of us who went to college learned how to learn. If people ever make the jump from being taught to learning how to learn for themselves, they typically do that in undergraduate college. However, this is far too unreliable; too many people who pass through college are still waiting to be taught, rather than taking ownership of their learning. Moreover, we need that transition happening in high school. We need all citizens, whether or not they attend college, being able to own and direct their learning.

Middle-Class Finishing School

In fact, everyone has been talking out of both sides of their mouths on the subject of college for a very long time.

As late as 1980, kids were being told to get a college degree and get a good job with a large company. I worked with people in technology who had degrees in English or sociology who had been hired by Bell Labs and working in technology-intensive roles. The important thing was that you had a degree.

College was, in fact, a middle-class finishing school. To sell for Xerox, you needed a degree. After all, you would be selling to people who mostly had college degrees. The Xerox business card would get you in the door. The important thing was, having got in the door, that you not blow the sale. The most probable way for you to navigate the completion of the sale was to have common shared experiences with your buyers. The people buying from you most likely went to college. Thus, a degree was required.

The large corporation could afford to carry you for the 2-3 years it would take for you to unlearn what you learned in college and become effective in your corporate environment. Thereafter, you would earn your keep.

But corporate downsizing began in earnest around 1985. Suddenly, there were not an abundance of good entry-level jobs with large corporations. By 1990, there were more jobs being created in companies owned by women than in the Fortune 500. This fundamentally changed the game.

Smaller companies can’t carry college graduates for 2-3 years while they figure out which end is up. In knowledge work, if you have to tell me how to do the task you need me to do, it’s easier for you to just do it yourself. I would be a hindrance to you; you could not tolerate me on the payroll. Meanwhile, colleges still don’t want to provide “vocational training.” The typical undergraduate program prepares a student to be a grad student in that subject, not to go out and deliver value in the workplace.

The people who are mortgaging themselves to the hilt to get their kids into “good schools” are fighting the last war. And losing. Badly.

What College Should Do

The state workers who help the unemployed are now saying that the average person will have 5-7 careers in her/his working life. That’s careers, not jobs. College needs to prepare students for this. Only a minority can possibly have academic careers or become artists, musicians or other creators of culture. The majority will have to make their living working in commercial enterprises.

Most college graduates will have to amortize their college learning and their college costs over 8-10 years, not 30+ years like some older people have been able to do. After 8-10 years, they may have to go back for an advanced degree to prepare for the next turn of the wheel.

Most college programs are centered around:

- Core courses to feed starving departments, dressed up as “well-roundedness”;

- Preparation to be a grad student in the major field of study.

Much of the core program is based on survey courses that emphasize spitback: memorization and regurgitation of whatever is of interest to the teacher. The students promptly forget it as soon as the final exam is turned in.

What we really want from college is:

- Preparation for some useful skills that someone will compensate you for;

- Understanding of the principles behind the skills (this is what separates an engineer from a technician);

- Ability to learn, so that the graduate can pick up the next set of skills on her/his own.

We should be able to obtain this in 3 years instead of 4. This would have people standing on their own two feet a year earlier. It’s good for their self-esteem.

Isn’t College Required for a Good Job?

The standard message has been that the earnings of college graduates have left the earnings of non-graduates behind. This has become the evergreen justification for doing whatever it takes to pay for college. But look deeper.

Here is a 2011 article from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, titled “Are Underemployed Graduates Displacing Nongraduates?”:

http://www.clevelandfed.org/research/trends/2011/0711/01labmar.cfm

We looked at data that could reflect this trend and found that college graduates are in fact becoming more prevalent in occupations that do not require a degree. The trend actually started before the recession, though it has, if anything, increased during the slowdown. Also, a few very-low-skilled occupations have seen a jump in college graduates during and after the recession. While other ongoing structural changes in the economy could be driving all of these trends in the data, they are consistent with the stories of educated people rolling down into mismatched positions.

So, let’s take the obvious and overworked target job: barista at a coffee shop. The average hourly wage, at the time of this writing, is $9. If you are allowed to work full time, you would make $18,000/year (Not all such employers want to allow that, because then they have to offer you the same benefits they offer the people at corporate). Having the college degree might allow you to beat out a competitor who did not attend college for that job.

But that is not the right way to analyze the issue. Let’s say you’ve borrowed $60,000 to attend college. That means you have a debt of $60,000 plus interest to cover with returns of $18,000 a year, out of which you also have to pay for food, clothing, housing, transporation and taxes. Depending on the state you live in, you may only take home $12,600 after taxes. Was college a good investment? I think not. I just checked and found market fixed rates between 6-7%. At 6% compounded monthly, a year’s interest on $60,000 is about $3,700. You’re going to have to be living in your parents’ basement to be able to keep up.

The barista example may seem a little extreme. But as the research report shows, this is not an edge case. There are many jobs that do not require college-level skills where college graduates are displacing non-graduates, but compensation is not moving up to offset the costs of college. The hiring manager would understandably rather hire a college graduate, and college graduates are available to be hired for non-college-graduate wages.

I know, no one goes to college to be a barista in a coffee shop. But that just begs the question: why do they go? We have come full circle.

College Loans

More importantly, after they go, and they have a boatload of debt they can’t repay, what do they do?

Begin with the end in mind.

— Stephen Covey, The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People

The only sensible reason to take out a loan for education is that you think you can pay it off, interest included, in “cheaper” dollars. The dollars are cheaper if they are easier to earn with your education than they were before you had the education.

Here is an example of what not to do: a 26-year-old graduate of NYU with a degree in religious and women’s studies and nearly $100,000 in student debt:

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/29/your-money/student-loans/29money.html

There is nothing she can do with that education that helps her get out from under that mountain of debt any faster.

I recently attended a presentation on the current state of consumer credit. Student debt is the only segment of consumer credit experiencing growth since 2008. More importantly, while 30% of the student loans that were originated in 2007 were cosigned, 70% of the loans originated in 2012 were. You can look forward to a massive transfer of wealth from families to colleges and banks in the future, as parents are tapped for loans that their kids are unable to repay.

Here is the inside-the-engine-room perspective:

http://www.insidearm.com/opinion/a-love-letter-from-your-student-loan-bill-collector/

Last summer [2010], it was announced that student debt achieved the distinction of being greater than that of credit card holders and even the victims of subprime mortgages.

As the author notes:

As many employers now pull credit reports on job applicants, our defaulting student loan applicant is almost automatically assured a “No, thank you” no matter how otherwise qualified they might be.

Lenders make loans with the expectation that they will be repaid. Lenders are not investors, gamblers or speculators. Lenders provide temporary use of funds for profit (interest) with the expectation that the debt will ultimately be repaid, with low risk of non-payment. Somebody is going to be on the hook for that money. It doesn’t matter if the student is dead:

From the first article:

Edwards had three student loans when he died, two federal and one private. The two federal government loans were forgiven within a month of his death. However, the private loan company is refusing to forgive the loan.

The two federal government loans were forgiven with taxpayer money. You and I paid his loans. Ain’t we nice? The private lender did not have access to taxpayer money.

“He was paying the loan bills when he died, but the balance is still over $10,000, and if I’m ever a couple days late on a payment, the calls keep coming until I pay,” Edwards told ABC News.

You cosigned the loan! What did you think that meant?

So What Do We Do?

Understand the new realities. College is not going to be the automatic entry point to a middle-class income and standard of living. Your child may graduate college, even with an engineering or technology-related degree, and be looking for work. Other degrees, such as English, psychology or art history, offer even less optimistic prospects of employment opportunities.

If your family is sufficiently well off that you can pay for the educational experience for it’s own sake, great! By all means, if it is what you want to do and you have the support of the people writing the checks, take advantage of the opportunity. For the rest of us, however, college is an investment and has to be evaluated as such.

Insist on your child getting a degree that offers a meaningful opportunity to enhance her earning power after graduation. No prospect of payback, no funding, period.

Children should not graduate high school without knowing what it takes to maintain their standard of living. They should know what they would have to earn to be able to buy the home they currently live in. They should have to research whether the careers that interest them would allow them to afford that home.

Avoid private loans. They are more difficult than any other debt to get rid of in bankruptcy. You are better of paying for college on a Visa card.

If you cosign a loan with your child, it’s like going into a business partnership with him. Is that something you are willing to do? You will need to be able to exercise controls over his spending and repayment, or you will be stuck with the debt. If you can’t see your way clear on that, don’t cosign the loan.

Am I calling for the youth of America to be turned into mercenaries, caring first and foremost about their ability to make money? Damn straight!

If you do go to college, you will be exposed to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs repeatedly. As the theory teaches, if you can’t meet basic needs like food, clothing and shelter, you won’t care about self-actualization.